Bayesian Thinking, MLE, MAP & Inference

- 🧭 A Curious Beginning

- Bayes’ Theorem and Conditional Probability

- Prior, Likelihood, and Posterior

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) vs. Maximum A Posteriori Estimation (MAP)

- Conjugate Priors

- Gaussian Processes (Intro)

- Bayesian Foundations in Modern Data Science

🧭 A Curious Beginning

In the quiet of 18th-century England, a modest Presbyterian minister named Thomas Bayes worked in obscurity. He wasn’t a celebrated scientist of his day. In fact, his only published work during his lifetime was theological. But after his death in 1761, his friend Richard Price discovered among Bayes’ papers an unfinished manuscript containing a radical idea:

How can we reason about a cause when all we observe is its effect?

This single question would lay the foundation for what we now call Bayesian inference—a method of updating beliefs in light of new evidence. Price published the work posthumously, and it quietly entered mathematical discourse. It wasn’t until Pierre-Simon Laplace, decades later, that the idea was fully embraced, extended, and given its modern mathematical form.

Laplace would go on to apply Bayesian reasoning to everything from astronomy to criminal justice. But one of his most famous thought experiments was deeply simple—almost poetic.

He asked: If the sun has risen every day for as long as we can remember, what is the probability that it will rise again tomorrow?

Using a now-classic Bayesian formula known as the rule of succession, he calculated:

\[P(\text{sun rises tomorrow}) = \frac{n + 1}{n + 2}\]If the sun has risen for 10,000 days, this gives a probability of 10,001 / 10,002—astonishingly close to 1, but never quite certain.

That’s the core of Bayesian thinking: we are never absolutely sure, but we grow more confident with every piece of evidence.

Bayes gave us the structure. Laplace gave us the scale. And what they left behind is more than a formula—it’s a way of seeing the world.

This blog picks up that thread: how to move from uncertainty to understanding, from prior to posterior, from belief to evidence-backed belief.

Because in a world where noise is abundant and decisions must be made, Bayesian inference offers more than just math—it offers clarity.

Bayesian inference treats unknown parameters as random variables and uses probability distributions to express uncertainty. This philosophical shift opens the door to a rich array of techniques and tools that power everything from spam filters to hyperparameter tuning in deep learning.

Bayes’ Theorem and Conditional Probability

Bayes’ Theorem is a foundational result in probability theory and statistics that relates conditional probabilities. Given two events \(A\) and \(B\) with \(P(B) > 0\), Bayes’ Theorem states:

\[P(A \mid B) = \frac{P(B \mid A) \cdot P(A)}{P(B)}\]In this formulation:

- \(P(A)\) is the prior probability of \(A\), reflecting our initial belief before observing \(B\).

- \(P(B \mid A)\) is the likelihood of observing \(B\) given \(A\).

- \(P(B)\) is the marginal probability of \(B\), integrated over all possibilities.

- \(P(A \mid B)\) is the posterior probability: our updated belief about \(A\) after observing \(B\).

This theorem is derived directly from the definition of conditional probability:

\[P(A \cap B) = P(A \mid B) P(B) = P(B \mid A) P(A)\]Rearranging gives:

\[P(A \mid B) = \frac{P(B \mid A) P(A)}{P(B)}\]In Bayesian statistics, this result is used to update beliefs about unknown parameters in light of new data. For continuous parameters, the theorem generalizes to:

\[P(\theta \mid D) = \frac{P(D \mid \theta) P(\theta)}{P(D)}\]Where:

- \(\theta\) is a parameter.

- \(D\) is observed data.

- \(P(\theta)\) is the prior distribution.

- \(P(D \mid \theta)\) is the likelihood.

- \(P(\theta \mid D)\) is the posterior distribution.

- \(P(D) = \int P(D \mid \theta) P(\theta) d\theta\) is the evidence or marginal likelihood.

Example: Diagnostic Testing

Suppose a rare disease affects 1% of the population. A diagnostic test has:

- Sensitivity (true positive rate): 99%

- Specificity (true negative rate): 95%

We want to compute the probability that a person has the disease given a positive test result.

Let \(D\) denote having the disease, and \(T\) denote a positive test. Then:

\[P(D \mid T) = \frac{P(T \mid D) P(D)}{P(T)}\] \[= \frac{0.99 \times 0.01}{(0.99 \times 0.01) + (0.05 \times 0.99)}\] \[= \frac{0.0099}{0.0099 + 0.0495}\] \[= \frac{0.0099}{0.0594}\] \[\approx 0.167\]So despite a highly accurate test, the probability of truly having the disease given a positive test result is only about 16.7%. This demonstrates the importance of the prior (base rate) in interpreting diagnostic results.

Python Code for the Example

# Bayesian disease diagnosis

P_disease = 0.01

P_pos_given_disease = 0.99

P_pos_given_no_disease = 0.05

P_no_disease = 1 - P_disease

P_pos = P_pos_given_disease * P_disease + P_pos_given_no_disease * P_no_disease

P_disease_given_pos = (P_pos_given_disease * P_disease) / P_pos

print(f"Posterior probability: {P_disease_given_pos:.4f}")

Visualization

The following visualization generalizes the example by showing how the posterior probability changes as the prior (disease prevalence) varies.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

prior_probs = np.linspace(0.001, 0.1, 100)

sensitivity = 0.99

specificity = 0.95

false_positive = 1 - specificity

posterior_probs = (sensitivity * prior_probs) / (

sensitivity * prior_probs + false_positive * (1 - prior_probs))

plt.plot(prior_probs, posterior_probs, label="P(Disease | Positive Test)")

plt.xlabel("Prior Probability of Disease")

plt.ylabel("Posterior Probability")

plt.title("Bayesian Update: Disease Diagnosis")

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

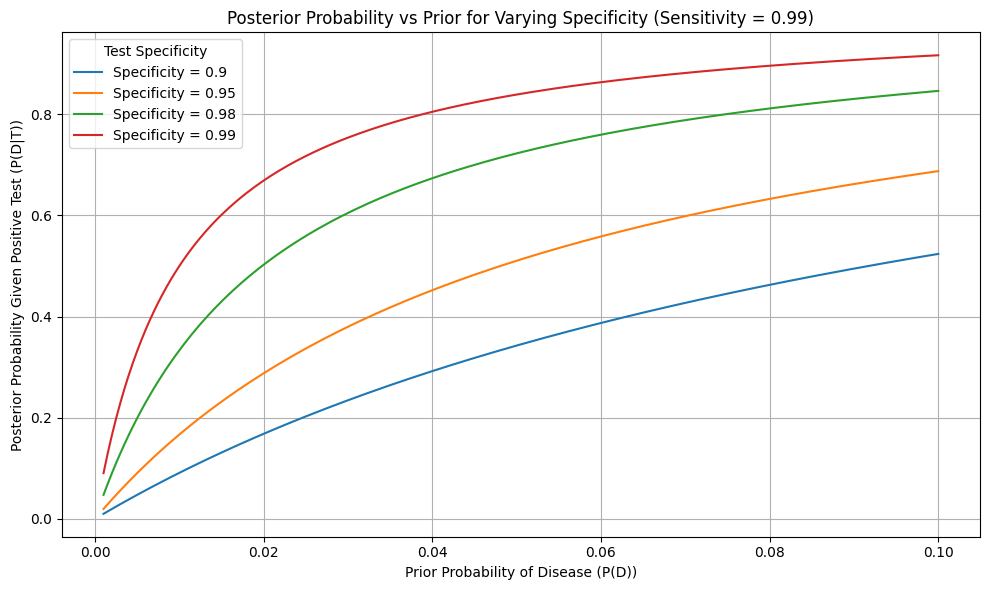

Figure: Posterior Probability vs Prior for Varying Specificity

This plot illustrates how the posterior probability of having a disease—after receiving a positive test result—varies based on two factors:

- The prior probability of the disease (x-axis), which corresponds to its prevalence in the population,

- And the specificity of the diagnostic test, or how well the test avoids false positives (multiple curves).

All curves assume a fixed sensitivity of 99% (i.e., the test correctly identifies almost all diseased cases).

-

When the disease is rare (e.g., prior probability below 1%), even a highly accurate test may produce a low posterior. This is because false positives dominate the marginal probability of a positive result at low prevalence.

-

As the prior probability increases (e.g., testing a high-risk group), the posterior probability increases sharply. This reflects how more confidence in the disease’s presence in the population strengthens the update from a positive result.

-

The higher the test specificity, the steeper the curve—and the stronger the belief update. With 99% specificity, a positive test leads to much higher posterior probabilities compared to 90% specificity, especially when the prior is low.

Applications in Data Science

Bayes’ Theorem is a pillar in many areas of applied machine learning and data science:

- Naive Bayes Classifiers: Used in email spam detection, text classification, and sentiment analysis.

- Medical Diagnostic Systems: Estimate disease probabilities as symptoms and test results accumulate.

- Bayesian A/B Testing: Provides posterior distributions over conversion rates instead of binary conclusions.

- Credit Scoring and Fraud Detection: Updates risk estimates in real-time based on user behavior.

It provides a mathematically sound, interpretable, and adaptive approach to reasoning and decision-making under uncertainty.

Prior, Likelihood, and Posterior

In the Bayesian framework, statistical inference is built on the principle of updating beliefs about parameters based on observed data. This belief is represented mathematically using probability distributions and updated using Bayes’ Theorem. The process relies on three central components:

- The prior: our belief about the parameter before seeing data,

- The likelihood: the probability of observing the data given a specific value of the parameter,

- The posterior: the revised belief after combining the prior and the likelihood.

Let us denote the unknown parameter by \(\theta\), and the observed data by \(D = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}\). Then:

\[P(\theta \mid D) = \frac{P(D \mid \theta) \cdot P(\theta)}{P(D)}\]This is Bayes’ Theorem applied to parameter estimation, where:

- \(P(\theta)\) is the prior distribution,

- \(P(D \mid \theta)\) is the likelihood,

- \(P(D)\) is the marginal likelihood or evidence,

- \(P(\theta \mid D)\) is the posterior.

Prior Distribution

The prior distribution \(P(\theta)\) expresses our belief or uncertainty about the parameter \(\theta\) before observing any data. Mathematically, the prior is a probability density function (pdf) over the domain of \(\theta\):

\[\int P(\theta) \, d\theta = 1\]This prior may be:

- Informative: When strong domain knowledge is available.

- Uninformative or weakly informative: To allow data to dominate inference.

- Subjective: Based on expert intuition or empirical insight.

The specific form of the prior depends on the nature of the parameter:

▸ Beta Prior (for probabilities \(\theta \in [0, 1]\)):

\[P(\theta) = \frac{1}{B(\alpha, \beta)} \theta^{\alpha - 1}(1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1}\]Where \(\alpha, \beta > 0\) are shape parameters, and \(B(\alpha, \beta)\) is the Beta function:

\[B(\alpha, \beta) = \int_0^1 \theta^{\alpha - 1} (1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1} \, d\theta\]This distribution is commonly used as a prior for binary outcomes and proportions. Its mean and variance are:

\[\mathbb{E}[\theta] = \frac{\alpha}{\alpha + \beta}, \quad \text{Var}(\theta) = \frac{\alpha \beta}{(\alpha + \beta)^2 (\alpha + \beta + 1)}\]▸ Gaussian Prior (for real-valued \(\theta\)):

\[P(\theta) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left( -\frac{(\theta - \mu)^2}{2\sigma^2} \right)\]Used in models like Bayesian linear regression or Gaussian processes, this prior expresses belief that \(\theta\) is centered around \(\mu\) with spread controlled by variance \(\sigma^2\).

▸ Uniform Prior (non-informative):

If nothing is known about \(\theta\) within an interval \([a, b]\):

\[P(\theta) = \frac{1}{b - a}, \quad \text{for } \theta \in [a, b]\]This flat prior assumes all values in \([a, b]\) are equally likely.

Likelihood Function

The likelihood function \(P(D \mid \theta)\) represents how plausible the observed data is for different values of the parameter \(\theta\). While the prior is independent of the data and reflects belief, the likelihood is derived from a data-generating model—a statistical assumption about how the data arises conditional on \(\theta\).

Formally, if the data consists of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) samples:

\[D = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}, \quad x_i \sim P(x \mid \theta)\]Then the likelihood becomes:

\[P(D \mid \theta) = \prod_{i=1}^n P(x_i \mid \theta)\]This is not a probability distribution over \(\theta\), but a function of \(\theta\) with data held fixed.

▸ Example: Bernoulli/Binomial Likelihood

Suppose each observation is a binary outcome (success/failure), modeled as a Bernoulli trial:

\[x_i \sim \text{Bernoulli}(\theta), \quad \text{so } P(x_i \mid \theta) = \theta^{x_i} (1 - \theta)^{1 - x_i}\]If we observe \(k\) successes in \(n\) trials, then:

\[P(D \mid \theta) = \prod_{i=1}^n \theta^{x_i} (1 - \theta)^{1 - x_i} = \theta^k (1 - \theta)^{n - k}\]This expression is the likelihood function, which evaluates how consistent various \(\theta\) values are with the observed success/failure count.

Posterior Distribution

The posterior distribution \(P(\theta \mid D)\) combines the prior and likelihood using Bayes’ Theorem:

\[P(\theta \mid D) = \frac{P(D \mid \theta) \cdot P(\theta)}{P(D)}\]Where the denominator is the marginal likelihood or evidence, ensuring that the posterior integrates to 1:

\[P(D) = \int P(D \mid \theta) \cdot P(\theta) \, d\theta\]▸ Beta Prior + Binomial Likelihood

Let’s assume:

- Prior: \(P(\theta) = \text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)\)

- Likelihood: \(P(D \mid \theta) = \theta^k (1 - \theta)^{n - k}\)

Then:

Unnormalized posterior:

\[P(\theta \mid D) \propto P(D \mid \theta) \cdot P(\theta)\] \[\propto \theta^k (1 - \theta)^{n - k} \cdot \theta^{\alpha - 1}(1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1}\] \[= \theta^{k + \alpha - 1}(1 - \theta)^{n - k + \beta - 1}\]This is the kernel of a Beta distribution:

\[P(\theta \mid D) = \text{Beta}(\alpha + k, \beta + n - k)\]This result highlights the convenience of conjugate priors: the prior and posterior belong to the same family, simplifying inference.

▸ Posterior Summary Statistics - Beta Distribution

Based on the posterior:

\[\theta \mid D \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha + k, \beta + n - k)\]where:

- \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are prior parameters,

- \(k\) is the number of observed successes,

- \(n\) is the total number of observations.

We derive:

1. Posterior Mean

If:

\[\theta \sim \text{Beta}(a, b)\]then the mean is given by:

\[\mathbb{E}[\theta] = \frac{a}{a + b}\]In our case, the posterior parameters are:

- \[a = \alpha + k\]

- \[b = \beta + n - k\]

So the posterior mean is:

\[\mathbb{E}[\theta \mid D] = \frac{\alpha + k}{\alpha + \beta + n}\]This is a convex combination of the prior mean and the observed frequency:

- Prior mean: \(\frac{\alpha}{\alpha + \beta}\)

- Observed frequency: \(\frac{k}{n}\)

As \(n\) increases, the posterior mean converges toward the sample mean \(k/n\), and the influence of the prior diminishes.

2. Posterior Variance

The variance of a Beta distribution \(\text{Beta}(a, b)\) is:

\[\text{Var}[\theta] = \frac{ab}{(a + b)^2 (a + b + 1)}\]Apply this to the posterior:

- \[a = \alpha + k\]

- \[b = \beta + n - k\]

Then:

\[\text{Var}[\theta \mid D] = \frac{(\alpha + k)(\beta + n - k)}{(\alpha + \beta + n)^2 (\alpha + \beta + n + 1)}\]This variance shrinks as \(n\) increases — reflecting increased confidence in our estimate of \(\theta\) after observing more data.

3. MAP Estimate (Posterior Mode)

The mode (maximum a posteriori estimate) of a Beta distribution \(\text{Beta}(a, b)\) is given by:

\[\theta_{\text{MAP}} = \frac{a - 1}{a + b - 2}, \quad \text{for } a > 1 \text{ and } b > 1\]Apply to the posterior:

- \[a = \alpha + k\]

- \[b = \beta + n - k\]

So:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \frac{\alpha + k - 1}{\alpha + \beta + n - 2}\]This estimate corresponds to the mode of the posterior distribution, and will differ from the mean unless the distribution is symmetric.

These quantities are critical in:

- Computing expected outcomes and uncertainty,

- Constructing Bayesian credible intervals,

- Making point predictions (e.g., MAP for classification),

- Visualizing posterior summaries.

▸ Posterior Derivation: Gaussian Likelihood and Gaussian Prior

In many data science tasks, we assume that the observed data is generated from a continuous process with Gaussian noise, and that our prior belief about the parameter is also normally distributed. This leads to one of the most well-known conjugate pairs: Gaussian-Gaussian inference (both the likelihood and prior are Gaussian — one of the most important and elegant conjugate models in Bayesian inference).

Let us assume:

- The parameter of interest is a real-valued scalar \(\theta\).

-

The observed data \(D = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}\) are i.i.d. samples from:

\[x_i \mid \theta \sim \mathcal{N}(\theta, \sigma^2)\]where \(\sigma^2\) is known (observation noise variance).

-

The prior belief about \(\theta\) is:

\[\theta \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_0, \tau^2)\]where \(\mu_0\) is the prior mean, and \(\tau^2\) is the prior variance.

Step 1: Likelihood Function

Given \(n\) i.i.d. observations \(x_1, ..., x_n\), the likelihood of the data given \(\theta\) is:

\[P(D \mid \theta) = \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp\left( -\frac{(x_i - \theta)^2}{2\sigma^2} \right)\]This is the product of Gaussians with the same mean \(\theta\) and fixed variance \(\sigma^2\).

Taking the log-likelihood:

\[\log P(D \mid \theta) = -\frac{n}{2} \log(2\pi\sigma^2) - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \theta)^2\]Let \(\bar{x} = \frac{1}{n} \sum x_i\). Then:

\[\sum (x_i - \theta)^2 = \sum (x_i - \bar{x} + \bar{x} - \theta)^2\] \[= \sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2 + n(\theta - \bar{x})^2\]So the likelihood becomes:

\[P(D \mid \theta) \propto \exp\left( -\frac{n}{2\sigma^2} (\theta - \bar{x})^2 \right)\]Which shows that the likelihood (up to normalization) is itself Gaussian:

\[\theta \mid D \propto \mathcal{N}(\bar{x}, \sigma^2 / n)\]Step 2: Prior

The prior is:

\[P(\theta) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\tau^2}} \exp\left( -\frac{(\theta - \mu_0)^2}{2\tau^2} \right)\]Step 3: Posterior Derivation

Bayes’ Theorem gives:

\[P(\theta \mid D) \propto P(D \mid \theta) \cdot P(\theta)\]Since both terms are exponentials of quadratics in \(\theta\), their product is proportional to another Gaussian:

Let’s expand both exponentials:

\[\log P(\theta \mid D) \propto -\frac{n}{2\sigma^2} (\theta - \bar{x})^2 - \frac{1}{2\tau^2} (\theta - \mu_0)^2\]Combine terms:

\[\log P(\theta \mid D)\] \[\propto -\frac{1}{2} \left[ \left( \frac{n}{\sigma^2} + \frac{1}{\tau^2} \right) \theta^2 - 2 \left( \frac{n\bar{x}}{\sigma^2} + \frac{\mu_0}{\tau^2} \right) \theta \right]\]This is the kernel of a Gaussian distribution with:

▸ Posterior Mean:

\[\mu_n = \frac{\frac{n}{\sigma^2} \bar{x} + \frac{1}{\tau^2} \mu_0}{\frac{n}{\sigma^2} + \frac{1}{\tau^2}}\]▸ Posterior Variance:

\[\sigma_n^2 = \left( \frac{n}{\sigma^2} + \frac{1}{\tau^2} \right)^{-1}\]Interpretation

- The posterior mean \(\mu_n\) is a weighted average of the prior mean and sample mean, where the weights are proportional to their respective precisions (inverse variances).

- The posterior variance \(\sigma_n^2\) is always smaller than either the prior or the sample variance alone, reflecting increased certainty after combining information.

This Gaussian-Gaussian model forms the mathematical foundation of many applications:

- Bayesian Linear Regression: Each weight in a regression model has a Gaussian prior and is updated analytically with Gaussian likelihoods. This allows regularization and closed-form uncertainty quantification.

- Bayesian Updating for Streaming Data: In online learning, new data incrementally shifts the posterior, making it a new prior — enabling scalable, memory-efficient learning.

- Sensor Fusion: In robotics and control systems, Bayesian Gaussian updates allow combining noisy measurements from multiple sensors to produce more confident estimates.

- Kalman Filters: A specialized form of recursive Bayesian estimation based on Gaussian distributions used in tracking and forecasting.

Stepping back from this specific case, the same pattern—prior, likelihood, and posterior—runs through the entire Bayesian approach.

- The prior captures what we know (or assume) before seeing any data.

- The likelihood tells us how compatible the data is with different parameter values.

- The posterior combines both to give us a data-informed belief about the parameter.

In data science, this allows:

- Incorporating prior knowledge (from previous experiments, expert belief, or regulatory constraints),

- Updating beliefs incrementally as more data becomes available,

- Quantifying uncertainty through full distributions instead of point estimates.

This foundation underlies a wide range of Bayesian models — from Naive Bayes classifiers and probabilistic graphical models to Gaussian Processes and Bayesian neural networks.

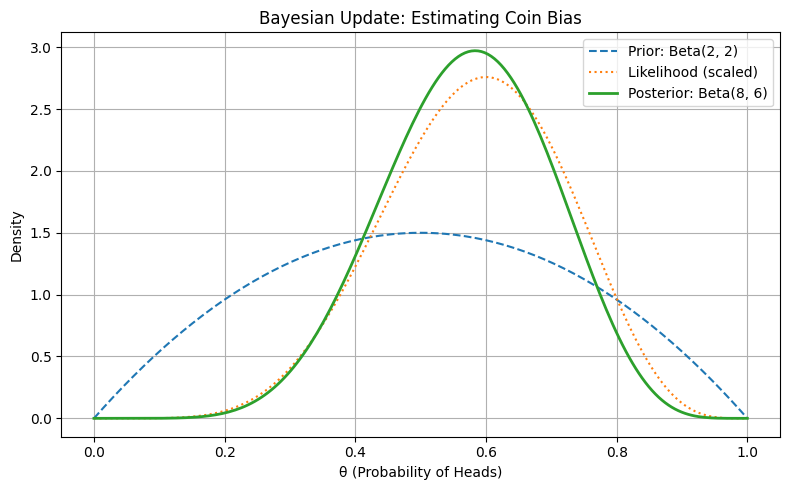

Example: Inferring Coin Bias

Let us assume we want to estimate the bias \(\theta\) (probability of heads) of a coin. Suppose we observe 10 tosses and get 6 heads and 4 tails. This is a Binomial process.

- Prior: Assume \(\theta \sim \text{Beta}(2, 2)\) — a weakly informative prior reflecting fairness.

-

Likelihood: For 6 heads out of 10 tosses,

\[P(D \mid \theta) = \binom{10}{6} \theta^6 (1 - \theta)^4\] -

Posterior: Since the Beta prior is conjugate to the Binomial likelihood, the posterior is:

\[\theta \mid D \sim \text{Beta}(2 + 6, 2 + 4) = \text{Beta}(8, 6)\]

This posterior reflects our updated belief about the coin’s bias after observing the data.

Visualization

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import beta

# Grid of theta values

theta = np.linspace(0, 1, 200)

# Prior: Beta(2, 2)

prior = beta.pdf(theta, 2, 2)

# Likelihood (up to proportionality): theta^6 * (1 - theta)^4

likelihood = theta**6 * (1 - theta)**4

likelihood /= np.trapz(likelihood, theta) # Normalize for plotting

# Posterior: Beta(8, 6)

posterior = beta.pdf(theta, 8, 6)

# Plotting

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.plot(theta, prior, label="Prior: Beta(2, 2)", linestyle="--")

plt.plot(theta, likelihood, label="Likelihood (scaled)", linestyle=":")

plt.plot(theta, posterior, label="Posterior: Beta(8, 6)", linewidth=2)

plt.title("Bayesian Update: Estimating Coin Bias")

plt.xlabel("θ (Probability of Heads)")

plt.ylabel("Density")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Figure: Bayesian Update: Estimating Coin Bias

This visualization shows how the prior belief and the observed data interact to form a posterior that reflects both — centered slightly above 0.5 due to the 6 observed heads.

Applications in Data Science

This prior-likelihood-posterior triad is a universal framework used across many data science workflows:

Bayesian A/B Testing

- Prior: Encodes historical conversion rates for variants.

- Likelihood: Comes from observed clicks or conversions (e.g., Binomial model).

- Posterior: Used to make probabilistic comparisons like \(P(\theta_A > \theta_B \mid \text{data})\).

This leads to more robust and interpretable decisions compared to traditional p-values.

Bayesian Regression

- Prior: Places distributions (e.g., Normal) over regression coefficients.

- Likelihood: Based on residuals from training data.

- Posterior: Yields not just point estimates, but full predictive intervals — crucial for risk-aware applications like pricing, forecasting, or credit scoring.

Fraud Detection

- Prior: Reflects expected fraud rate (e.g., from industry benchmarks).

- Likelihood: Comes from behavioral or transactional data.

- Posterior: Quantifies the probability of fraud for new transactions in real time.

Recommender Systems

- Prior: Reflects assumed user preferences or item popularity.

- Likelihood: Derived from user-item interaction data (ratings, clicks).

- Posterior: Enables personalized predictions with uncertainty quantification, improving exploration in recommendation.

The combination of prior beliefs and observed evidence, culminating in a posterior, provides a powerful and flexible inference engine. This Bayesian updating mechanism equips data scientists to not only make predictions but also understand their confidence in those predictions — a critical capability in domains where decisions have consequences.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) vs. Maximum A Posteriori Estimation (MAP)

One of the central challenges in statistical inference is the estimation of model parameters from observed data. Two important frameworks for parameter estimation are Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) and Maximum A Posteriori Estimation (MAP). While both aim to select parameter values that explain the data well, they differ in how they incorporate prior knowledge.

MLE derives purely from the likelihood function, whereas MAP is based on the full Bayesian posterior distribution. Their distinction becomes particularly meaningful in the presence of prior information, limited data, or regularization constraints.

MLE: Derivation and Explanation

Let \(D = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}\) be a set of i.i.d. observations drawn from a distribution parameterized by \(\theta\).

The likelihood function is:

\[L(\theta \mid D) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} P(x_i \mid \theta)\]Taking logs, the log-likelihood becomes:

\[\ell(\theta) = \log L(\theta \mid D) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log P(x_i \mid \theta)\]The Maximum Likelihood Estimator is the value of \(\theta\) that maximizes the log-likelihood:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MLE}} = \arg\max_\theta \, \ell(\theta)\]MLE Derivation: Bernoulli Case

Suppose each \(x_i\) is a Bernoulli trial with success probability \(\theta\). Then:

\[P(x_i \mid \theta) = \theta^{x_i} (1 - \theta)^{1 - x_i}\]So the log-likelihood becomes:

\[\ell(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \left[ x_i \log \theta + (1 - x_i) \log(1 - \theta) \right]\]Let:

- \(k = \sum_{i=1}^n x_i\) be the number of successes,

- \(n - k\) be the number of failures.

Then:

\[\ell(\theta) = k \log \theta + (n - k) \log(1 - \theta)\]To maximize, differentiate with respect to \(\theta\) and set the derivative to zero:

\[\frac{d\ell}{d\theta} = \frac{k}{\theta} - \frac{n - k}{1 - \theta} = 0\]Solving:

\[\frac{k}{\theta} = \frac{n - k}{1 - \theta} \Rightarrow k (1 - \theta) = (n - k) \theta\]Expanding:

\[k - k\theta = n\theta - k\theta \Rightarrow k = n\theta \Rightarrow \hat{\theta}_{\text{MLE}} = \frac{k}{n}\]MAP: Derivation and Explanation

In the Bayesian framework, we update our belief about \(\theta\) after observing \(D\) using Bayes’ Theorem:

\[P(\theta \mid D) = \frac{P(D \mid \theta) P(\theta)}{P(D)}\]The MAP estimator is:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \arg\max_\theta \, P(\theta \mid D)\] \[= \arg\max_\theta \, P(D \mid \theta) P(\theta)\]Taking logarithms:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \arg\max_\theta \left[ \log P(D \mid \theta) + \log P(\theta) \right]\]This formulation shows that MAP estimation is equivalent to MLE with a regularization term derived from the prior.

- If \(P(\theta)\) is uniform (uninformative), then MAP reduces to MLE.

- If \(P(\theta)\) is Gaussian, the log-prior is quadratic and acts like L2 regularization.

MAP Derivation: Bernoulli Likelihood and Beta Prior

Let:

- Likelihood: \(P(D \mid \theta) \propto \theta^k (1 - \theta)^{n - k}\)

- Prior: \(P(\theta) = \text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta) \propto \theta^{\alpha - 1}(1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1}\)

Then:

\[P(\theta \mid D) \propto \theta^{k + \alpha - 1}(1 - \theta)^{n - k + \beta - 1}\]This is a Beta posterior: \(\text{Beta}(k + \alpha, n - k + \beta)\).

To find the MAP estimate (mode of the Beta distribution), we differentiate the log-posterior:

\[\log P(\theta \mid D)\] \[= (k + \alpha - 1) \log \theta + (n - k + \beta - 1) \log(1 - \theta)\]Take derivative and set to zero:

\[\frac{d}{d\theta} \log P(\theta \mid D)\] \[= \frac{k + \alpha - 1}{\theta} - \frac{n - k + \beta - 1}{1 - \theta}\] \[= 0\]Solving:

\[\frac{k + \alpha - 1}{\theta}\] \[= \frac{n - k + \beta - 1}{1 - \theta} \Rightarrow (k + \alpha - 1)(1 - \theta)\] \[= (n - k + \beta - 1)\theta\]Expanding:

\[k + \alpha - 1 - (k + \alpha - 1)\theta = (n - k + \beta - 1)\theta\]Move terms:

\[k + \alpha - 1 = \theta \left[(n - k + \beta - 1) + (k + \alpha - 1)\right]\] \[= \theta (n + \alpha + \beta - 2)\]Thus, the MAP estimate is:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \frac{k + \alpha - 1}{n + \alpha + \beta - 2}\]When \(\alpha = \beta = 1\) (uniform prior), MAP reduces to MLE:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \frac{k}{n}\]Bernoulli Example with Beta Prior

Suppose we toss a coin \(n = 5\) times and observe \(k = 3\) heads. Let \(\theta\) be the probability of heads.

-

The likelihood is:

\[P(k \mid \theta) = \binom{5}{3} \theta^3 (1 - \theta)^2 \propto \theta^3 (1 - \theta)^2\] -

The prior is a Beta distribution: \(P(\theta) \propto \theta^{\alpha - 1} (1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1}\).

Let’s use \(\text{Beta}(2, 2)\), so:

\[P(\theta) \propto \theta (1 - \theta)\] -

The posterior is then:

\[P(\theta \mid D) \propto \theta^3 (1 - \theta)^2 \cdot \theta (1 - \theta) = \theta^4 (1 - \theta)^3\]

This corresponds to a Beta(5, 4) posterior.

-

The MLE is:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MLE}} = \frac{k}{n} = \frac{3}{5} = 0.6\] -

The MAP estimate (mode of Beta(5,4)) is:

\[\hat{\theta}_{\text{MAP}} = \frac{5 - 1}{5 + 4 - 2} = \frac{4}{7} \approx 0.571\]

Visualization

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import beta

theta_vals = np.linspace(0, 1, 200)

# Likelihood (up to constant)

k, n = 3, 5

likelihood = theta_vals**k * (1 - theta_vals)**(n - k)

likelihood /= np.trapz(likelihood, theta_vals)

# Prior: Beta(2, 2)

prior = beta.pdf(theta_vals, 2, 2)

# Posterior: Beta(5, 4)

posterior = beta.pdf(theta_vals, 5, 4)

# Estimates

theta_mle = k / n

theta_map = (5 - 1) / (5 + 4 - 2)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.plot(theta_vals, likelihood, label="Likelihood (MLE)", linestyle="--")

plt.plot(theta_vals, prior, label="Prior: Beta(2,2)", linestyle=":")

plt.plot(theta_vals, posterior, label="Posterior: Beta(5,4)", linewidth=2)

plt.axvline(theta_mle, color="gray", linestyle="--", label=f"MLE: {theta_mle:.2f}")

plt.axvline(theta_map, color="black", linestyle=":", label=f"MAP: {theta_map:.2f}")

plt.title("MAP vs MLE Estimation for Coin Bias")

plt.xlabel("θ (Probability of Heads)")

plt.ylabel("Density")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

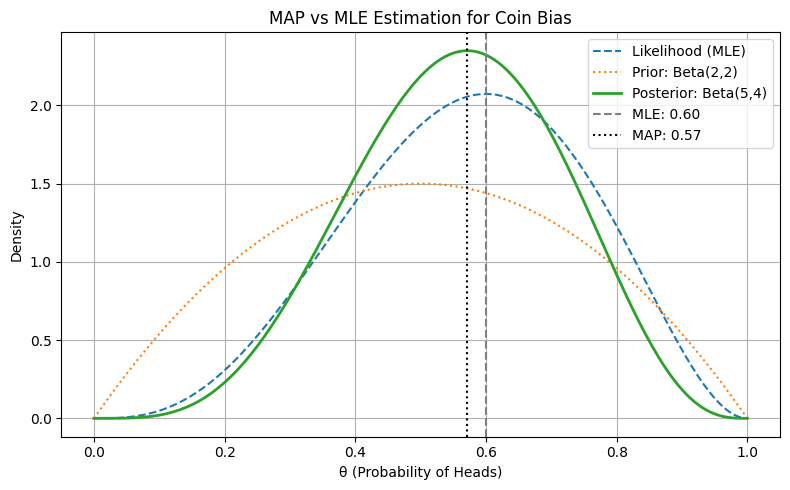

The plot below demonstrates how Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) and Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) estimation differ when estimating the bias \(\theta\) of a coin (i.e., the probability of getting heads).

The goal is to estimate the most likely value of \(\theta\) based on:

- A prior belief about the coin’s fairness (a Beta distribution),

- A small sample of observed data (3 heads out of 5 tosses).

Figure: MAP vs MLE Estimation for Coin Bias

- Prior: A \(\text{Beta}(2,2)\) distribution, centered at 0.5, representing a mild belief that the coin is fair.

- Observed Data: 5 tosses, with 3 heads and 2 tails.

-

Likelihood: Based on the Binomial model:

\[P(D \mid \theta) \propto \theta^3 (1 - \theta)^2\] -

Posterior: With a conjugate Beta prior and Binomial likelihood, the posterior becomes:

\[\text{Beta}(\alpha + k, \beta + n - k) = \text{Beta}(5, 4)\]

Inferences we can make:

-

MLE Ignores Prior Knowledge:

The likelihood peaks at \(\theta = 0.6\)—which is simply the empirical ratio \(k/n = 3/5\). This is the MLE and represents the estimate purely from data. -

MAP Blends Prior and Data:

The posterior peaks at around \(\theta = 0.571\). The MAP estimate is slightly pulled toward the prior mean (0.5) compared to MLE. This reflects the influence of the prior, which assumed the coin is more likely to be fair. -

Priors Act as Regularizers:

The MAP estimator essentially acts like a regularized version of MLE—biasing the estimate toward prior beliefs, especially when sample size is small. With more data, the MAP and MLE would converge. -

Posterior Reflects Uncertainty More Holistically:

Compared to the sharper likelihood, the posterior incorporates both data and prior uncertainty, making it slightly wider and smoother—especially relevant in low-data settings. -

MAP ≠ MLE When Priors Are Informative:

This visualization is a concrete demonstration of how MAP ≠ MLE when the prior is not flat. It’s a critical concept when explaining regularization, Bayesian learning, or when modeling with limited data.

To summarize, this plot provides a visual comparison of two common estimation strategies:

- MLE: Trusts only the data.

- MAP: Trusts both the data and a prior belief.

When data is scarce (as it often is in real-world applications), the regularization effect of the prior becomes particularly useful. Bayesian methods provide a principled way to implement this regularization through posterior inference, and this example makes that visible and intuitive.

Applications in Data Science

Logistic Regression

MLE finds weights that minimize the negative log-likelihood. However, MAP estimation adds a prior over the weights (usually Gaussian), which leads to regularized logistic regression:

\[\hat{w}_{\text{MAP}}\] \[= \arg\min_w \left[ \sum_i \log(1 + e^{-y_i x_i^T w}) + \frac{\lambda}{2} \|w\|^2 \right]\]This helps control overfitting, especially in high-dimensional spaces.

Bayesian Linear Regression

In linear regression, MAP estimation with a Gaussian prior yields Ridge regression:

\[\hat{\beta}_{\text{MAP}} = \arg\min_{\beta} \left[ \|y - X\beta\|^2 + \lambda \|\beta\|^2 \right]\]This provides stability when data is sparse or multicollinearity is present.

Cold Start and Sparse Data Problems

MAP estimators are essential when:

- Data is limited (e.g., few clicks or ratings per user).

- You want to encode prior beliefs (e.g., users prefer popular items).

- You want robust, regularized predictions rather than overfitting.

MAP allows us to “pull” parameter estimates towards prior expectations when data is insufficient, making it highly useful in recommender systems and early-stage modeling.

Conjugate Priors

One of the elegant outcomes in Bayesian inference is that certain choices of priors lead to mathematically convenient posteriors. When a prior and its corresponding posterior distribution belong to the same family, the prior is said to be a conjugate prior for the likelihood function.

This property is not just algebraic elegance — it enables closed-form updates, analytical tractability, and efficient implementation in sequential or real-time inference systems.

Formal Definition

A prior distribution \(P(\theta)\) is said to be conjugate to a likelihood function \(P(D \mid \theta)\) if the posterior \(P(\theta \mid D)\) is in the same family of distributions as the prior.

That is:

\[\text{If } P(\theta) \in \mathcal{F} \text{ and } P(\theta \mid D) \in \mathcal{F} \text{ as well,}\] \[\text{ then } P(\theta) \text{ is conjugate.}\]Some classic conjugate prior–likelihood pairs include:

| Likelihood | Conjugate Prior | Posterior |

|---|---|---|

| Bernoulli/Binomial | Beta | Beta |

| Poisson | Gamma | Gamma |

| Normal (known variance) | Normal | Normal |

| Multinomial | Dirichlet | Dirichlet |

Why It Matters

Conjugate priors greatly simplify Bayesian analysis. When using a conjugate prior:

- Posterior distributions can be derived analytically.

- Bayesian updating can be done incrementally and efficiently.

- The form of the prior helps encode domain knowledge (e.g., belief in fairness, expected rates, etc.)

This is particularly useful in low-latency systems like online learning, A/B testing pipelines, and probabilistic graphical models where recomputation must be fast.

Example: Beta Prior for a Bernoulli/Binomial Likelihood

Suppose we are modeling a binary outcome — say, a coin flip. The outcome is modeled as a Bernoulli process with unknown probability of success \(\theta\).

Likelihood

Let \(x_1, \dots, x_n\) be i.i.d. Bernoulli trials with parameter \(\theta\). The likelihood is:

\[P(D \mid \theta) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \theta^{x_i}(1 - \theta)^{1 - x_i}\]Let \(k = \sum x_i\) (number of successes), so:

\[P(D \mid \theta) = \theta^k (1 - \theta)^{n - k}\]Prior

We choose a Beta prior:

\[P(\theta) = \frac{1}{B(\alpha, \beta)} \theta^{\alpha - 1}(1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1}\]Where \(\alpha, \beta > 0\), and \(B(\alpha, \beta)\) is the Beta function:

\[B(\alpha, \beta) = \int_0^1 t^{\alpha - 1} (1 - t)^{\beta - 1} dt\]Posterior

Using Bayes’ theorem:

\[P(\theta \mid D) \propto P(D \mid \theta) \cdot P(\theta)\] \[= \theta^k (1 - \theta)^{n - k} \cdot \theta^{\alpha - 1} (1 - \theta)^{\beta - 1}\] \[= \theta^{\alpha + k - 1} (1 - \theta)^{\beta + n - k - 1}\]Thus, the posterior is:

\[P(\theta \mid D) = \text{Beta}(\alpha + k, \beta + n - k)\]This clean and efficient update rule makes the Beta distribution the conjugate prior for the Bernoulli and Binomial likelihood.

Interpretation

Each time we observe new data in the form of successes and failures (e.g., from a Bernoulli or Binomial process), we can update the parameters of the Beta prior in a simple, additive way. This is one of the most intuitive benefits of conjugate priors.

If the prior is \(\text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)\), and we observe:

- \(k\) successes,

- \(n - k\) failures,

then the posterior becomes \(\text{Beta}(\alpha', \beta')\), where:

\[\alpha' = \alpha + k\] \[\beta' = \beta + (n - k)\]This rule makes it easy to perform sequential updates — as new observations come in, we can incrementally revise our posterior without needing to recompute from scratch. It’s especially valuable in streaming, online learning, and real-time probabilistic systems.

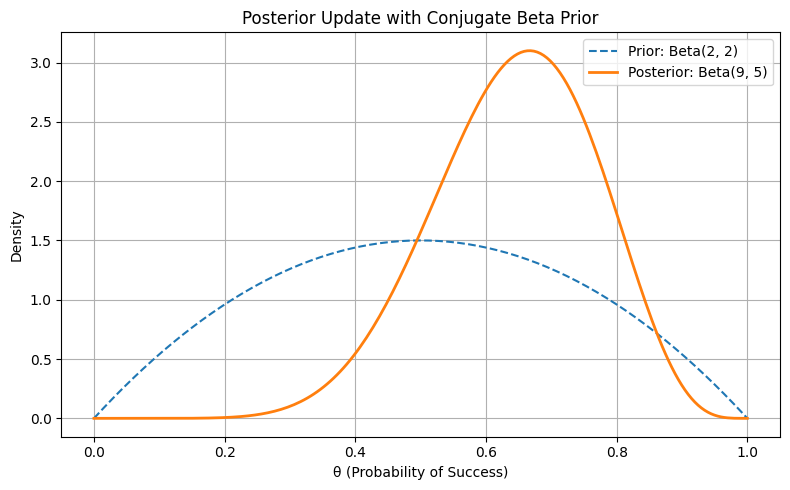

Visualization

To better understand how conjugate priors simplify Bayesian updating, let’s visualize how a Beta prior gets updated after observing data from a Binomial process. In this example, we assume a weakly informative prior belief about a coin’s fairness (Beta(2, 2)) and then observe 10 coin tosses with 7 heads. Because the Beta distribution is conjugate to the Binomial likelihood, we can compute the posterior analytically—resulting in another Beta distribution with updated parameters. This makes it easy to see how the prior and data interact to form the posterior.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import beta

# Observed data: 7 successes in 10 trials

k, n = 7, 10

failures = n - k

# Prior: Beta(2, 2)

alpha_prior = 2

beta_prior = 2

# Posterior: Beta(2 + 7, 2 + 3) = Beta(9, 5)

alpha_post = alpha_prior + k

beta_post = beta_prior + failures

theta = np.linspace(0, 1, 200)

prior_pdf = beta.pdf(theta, alpha_prior, beta_prior)

posterior_pdf = beta.pdf(theta, alpha_post, beta_post)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.plot(theta, prior_pdf, label="Prior: Beta(2, 2)", linestyle="--")

plt.plot(theta, posterior_pdf, label="Posterior: Beta(9, 5)", linewidth=2)

plt.title("Posterior Update with Conjugate Beta Prior")

plt.xlabel("θ (Probability of Success)")

plt.ylabel("Density")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

This visualization shows how the prior belief (centered at 0.5) gets updated based on data favoring higher success probability.

Figure: Posterior Update with Conjugate Beta Prior

This plot compares two distributions:

- The prior: \(\text{Beta}(2, 2)\) — symmetric around 0.5, representing mild uncertainty about the coin being fair.

- The posterior: \(\text{Beta}(9, 5)\) — updated belief after observing 7 heads out of 10 flips.

What’s Happening Under the Hood:

- The prior parameters \(\alpha = 2, \beta = 2\) represent 1 prior success and 1 prior failure (Beta counts start from one).

-

After observing the data, we apply the conjugate update:

\[\alpha_{\text{posterior}} = \alpha_{\text{prior}} + k = 2 + 7 = 9\] \[\beta_{\text{posterior}} = \beta_{\text{prior}} + (n - k) = 2 + 3 = 5\] - The posterior is thus \(\text{Beta}(9, 5)\) — a distribution that favors \(\theta > 0.5\), aligning with the observed data, but still shaped by the prior.

The Plot Shows:

- The prior curve is flat-ish and centered at 0.5, reflecting openness to a range of \(\theta\) values.

- The posterior curve is steeper and shifted right, peaking around \(\theta \approx 0.64\).

- The update is not overconfident — the posterior still acknowledges uncertainty but now leans toward higher \(\theta\) based on evidence.

Inferences to make:

-

Bayesian updating is additive and intuitive:

With conjugate priors, updating is just a matter of adjusting counts. This keeps the math clean and interpretability high. -

The prior influences the posterior more when data is limited:

In this example, with only 10 trials, the prior still has a noticeable effect. Had we used Beta(1, 1), the posterior would shift even further toward the empirical proportion (0.7). -

Posterior reflects a refined belief:

The posterior balances prior belief and observed data, yielding a distribution that’s sharper than the prior but not as sharp as the maximum likelihood would suggest. -

This approach scales well:

The same logic applies whether you’re flipping a coin, testing an email subject line, or modeling click-through rates. That’s why Beta-Binomial updates are widely used in A/B testing, online learning, and Bayesian filtering.

Applications in Data Science

Bayesian A/B Testing

In online experimentation:

- Each version has a Beta prior over its conversion rate.

- New data updates the posterior in real-time.

- This allows comparing \(P(\theta_A > \theta_B \mid \text{data})\) directly, unlike frequentist p-values.

Conjugate priors enable this with fast, closed-form updates and interpretable distributions.

Real-Time User Modeling

Click-through rates, open rates, fraud likelihoods — all modeled as binary outcomes. Beta priors can be updated on-the-fly as new data arrives, powering systems like:

- Dynamic personalization

- Spam filtering

- Risk scoring in transactions

Bayesian Filtering and Probabilistic Robotics

In robotics and control systems, conjugate priors are used for recursive Bayesian filters (e.g., Kalman filters, where Gaussians are conjugate to themselves) to update beliefs about position, velocity, or sensor noise.

Conjugate priors marry theory and practice in Bayesian modeling. They offer a principled way to integrate domain knowledge, perform fast posterior updates, and maintain mathematical elegance — making them an indispensable tool in the probabilistic data scientist’s toolkit.

Gaussian Processes (Intro)

Gaussian Processes (GPs) offer a powerful and flexible framework for non-parametric Bayesian modeling. Unlike traditional models that learn a finite set of parameters (like coefficients in linear regression), GPs treat inference as learning a distribution over functions.

This makes them ideal when you not only want to predict a value but also quantify uncertainty about that prediction — a crucial requirement in safety-critical applications such as medical diagnostics, robotics, and autonomous systems.

What is a Gaussian Process?

A Gaussian Process is a collection of random variables, any finite number of which have a joint Gaussian distribution. It is completely specified by:

- A mean function \(m(x)\), and

- A covariance function or kernel \(k(x, x')\).

Formally, we write:

\[f(x) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x), k(x, x'))\]Where:

- \[m(x) = \mathbb{E}[f(x)]\]

- \[k(x, x') = \mathbb{E}[(f(x) - m(x))(f(x') - m(x'))]\]

This means that for any finite set of inputs \(x_1, \dots, x_n\), the function values \(f(x_1), \dots, f(x_n)\) follow a multivariate normal distribution:

\[[f(x_1), \dots, f(x_n)]^\top \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, K)\]Where:

- \[\mu_i = m(x_i)\]

- \[K_{ij} = k(x_i, x_j)\]

Gaussian Process Regression: Intuition

Let us consider a regression problem where we are given a dataset of \(n\) observed input-output pairs:

\[D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n\]We assume the outputs are generated from an unknown latent function \(f(x)\) with added Gaussian noise:

\[y_i = f(x_i) + \epsilon_i, \quad \epsilon_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_n^2)\]Our goal is to learn about \(f(x)\) — not as a fixed parametric model, but as a distribution over possible functions. This is where Gaussian Processes come into play.

A Gaussian Process (GP) is a prior over functions such that any finite collection of function values follows a multivariate Gaussian distribution:

\[f(x) \sim \mathcal{GP}(m(x), k(x, x'))\]Here:

- \(m(x) = \mathbb{E}[f(x)]\) is the mean function, often set to zero for simplicity.

- \(k(x, x') = \mathbb{E}[(f(x) - m(x))(f(x') - m(x'))]\) is the kernel or covariance function.

Given training inputs \(X = [x_1, ..., x_n]\) and outputs \(\mathbf{y} = [y_1, ..., y_n]^T\), and test inputs \(X_*\), the GP framework models the joint distribution of training and test outputs as:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{y} \\ \mathbf{f}_* \end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N} \left( \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} K(X, X) + \sigma_n^2 I & K(X, X_*) \\ K(X_*, X) & K(X_*, X_*) \end{bmatrix} \right)\]Where:

- \(K(X, X)\) is the \(n \times n\) covariance matrix for training inputs.

- \(K(X, X_*)\) is the \(n \times m\) cross-covariance between training and test inputs.

- \(K(X_*, X_*)\) is the \(m \times m\) covariance of the test inputs.

- \(\sigma_n^2 I\) adds noise to the diagonal (due to the assumed observational noise).

The posterior predictive distribution for the function values at test points is then given by:

\[\mathbf{f}_* \mid X, \mathbf{y}, X_* \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_*, \Sigma_*)\]Where:

-

Posterior mean:

\[\mu_* = K(X_*, X)[K(X, X) + \sigma_n^2 I]^{-1} \mathbf{y}\] -

Posterior covariance:

\(\Sigma_* = K(X_*, X_*) -\) \(K(X_*, X)[K(X, X) + \sigma_n^2 I]^{-1} K(X, X_*)\)

This formulation gives us both predictions (mean) and uncertainty (variance) at any set of new inputs.

The Role of the Kernel Function

The kernel function \(k(x, x')\) defines the covariance structure between the function values at different inputs. It encodes prior assumptions about the function’s properties — smoothness, periodicity, linearity, etc. The choice of kernel is crucial as it determines the shape of the functions the GP considers likely.

Here are some commonly used kernels:

1. Radial Basis Function (RBF) or Squared Exponential Kernel

This is the most widely used kernel due to its universal approximation properties and smoothness:

\[k(x, x') = \exp\left(-\frac{(x - x')^2}{2\ell^2}\right)\]- \(\ell\) is the length scale, controlling how quickly the function varies.

- Encourages infinitely differentiable, smooth functions.

- Implies that points closer in input space have highly correlated function values.

2. Matern Kernel

A generalization of the RBF kernel that allows for less smoothness:

\[k_\nu(r) = \frac{2^{1-\nu}}{\Gamma(\nu)} \left( \frac{\sqrt{2\nu}r}{\ell} \right)^\nu K_\nu \left( \frac{\sqrt{2\nu}r}{\ell} \right)\]- \[r = |x - x'|\]

- \(\nu\) controls smoothness: e.g., \(\nu = 1/2\) gives exponential kernel, \(\nu \to \infty\) recovers RBF.

- Suitable for modeling rougher, more realistic functions in real-world applications.

3. Dot Product (Linear) Kernel

Used when the function is expected to be linear:

\[k(x, x') = x^T x'\]- Equivalent to Bayesian linear regression.

- Doesn’t model nonlinearity unless combined with other kernels.

4. Periodic Kernel

Models functions with known repeating structure:

\[k(x, x') = \exp\left(-\frac{2 \sin^2(\pi |x - x'| / p)}{\ell^2}\right)\]- \(p\) controls the period, \(\ell\) controls smoothness.

- Ideal for seasonal data, time series, and cyclic behaviors.

Why Kernels Matter in Practice

The kernel acts as a prior over function space, shaping not only the kinds of functions the model will favor but also how information propagates across the input domain. Inference in a GP is guided entirely by the covariance implied by the kernel.

Choosing a kernel is a modeling decision — like choosing a neural network architecture or a basis function family — but in GPs, it’s probabilistically grounded. And importantly, it’s differentiable and tunable: you can learn kernel parameters (like \(\ell\)) by maximizing the marginal likelihood.

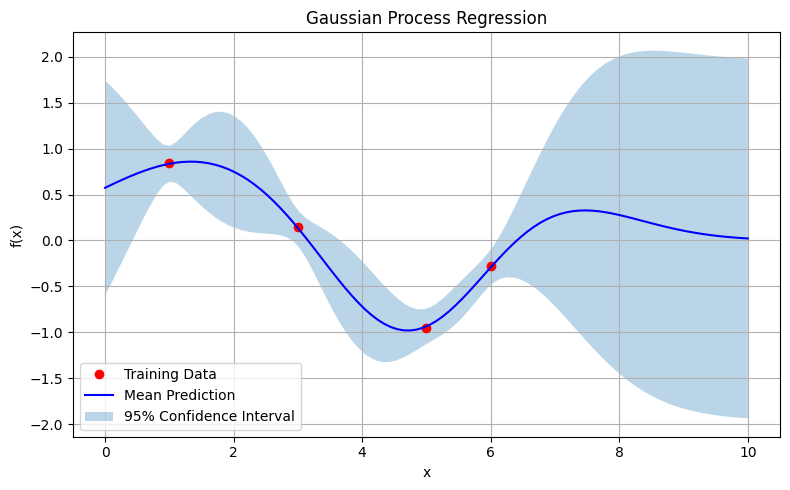

Visualization

To illustrate how Gaussian Processes model distributions over functions, let’s walk through a simple 1D regression example using scikit-learn. We’ll fit a GP to a small set of noisy training points, allowing it to not only predict the mean function but also provide a confidence interval that reflects its uncertainty. The GP is equipped with an RBF (Radial Basis Function) kernel, which assumes smoothness in the underlying function.

This example visually demonstrates one of the GP’s most powerful features: it can interpolate sparse data while expressing its uncertainty about regions it has not seen.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.gaussian_process import GaussianProcessRegressor

from sklearn.gaussian_process.kernels import RBF

# Training data (sparse)

X_train = np.array([[1], [3], [5], [6]])

y_train = np.sin(X_train).ravel()

# Define GP with RBF kernel

kernel = RBF(length_scale=1.0)

gp = GaussianProcessRegressor(kernel=kernel, alpha=1e-2)

gp.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predictive distribution at test points

X_test = np.linspace(0, 10, 100).reshape(-1, 1)

y_pred, sigma = gp.predict(X_test, return_std=True)

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.plot(X_train, y_train, 'ro', label='Training Data')

plt.plot(X_test, y_pred, 'b-', label='Mean Prediction')

plt.fill_between(X_test.ravel(), y_pred - 1.96 * sigma, y_pred + 1.96 * sigma,

alpha=0.3, label='95% Confidence Interval')

plt.title("Gaussian Process Regression")

plt.xlabel("x")

plt.ylabel("f(x)")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Figure: Gaussian Process Regression

The Plot Shows:

- Red dots represent the observed training data points.

- The blue line is the mean prediction of the Gaussian Process at every point in the input space.

-

The shaded region corresponds to a 95% confidence interval, calculated as:

\[\hat{f}(x) \pm 1.96 \cdot \sigma(x)\]where \(\hat{f}(x)\) is the predicted mean and \(\sigma(x)\) is the standard deviation from the posterior.

Insights we can infer from this are

-

Probabilistic Predictions, Not Just Point Estimates

Unlike traditional regressors (like polynomial or linear regression), the GP predicts a distribution over functions, not a single best fit. For each input \(x\), it returns a mean prediction and a measure of uncertainty. -

Uncertainty Reflects Data Coverage

The model is most confident (i.e., narrowest uncertainty band) near the observed data points, and increasingly uncertain as we move away from them. This is especially visible at the edges (near \(x = 0\) and \(x = 10\)), where the GP hasn’t seen any training data. -

The Role of the RBF Kernel

The RBF kernel assumes that points closer in input space produce similar outputs. It’s what gives the GP its smooth, wavy behavior. If a different kernel were used (e.g., linear or periodic), the shape of the mean and uncertainty band would change. - Handling Small Datasets Gracefully

Despite having only four training points, the GP constructs a smooth function that captures the structure of the underlying sine wave—without overfitting. This makes it particularly useful in low-data regimes like:- Experimental design,

- Bayesian optimization,

- Medical modeling, where samples are expensive.

- Interpretable Uncertainty

The shaded band gives us a principled way to quantify model confidence. Unlike confidence intervals in frequentist regression, which apply to the parameter estimate, the GP’s uncertainty is pointwise and interpretable: “Here’s how unsure the model is at this input.”

This showcases the core strength of Gaussian Processes: flexible, non-parametric regression with uncertainty quantification. By treating the prediction as a distribution over functions, the GP provides not only a best guess but also a principled expression of how much we trust that guess at each point. This property is crucial in settings where uncertainty is as important as accuracy.

This visualization illustrates:

- How GPs interpolate observed points with smooth curves,

- How prediction uncertainty grows away from the training data,

- And how the kernel controls the shape of the functions we consider probable.

Applications in Data Science

Bayesian Optimization

GPs are often used as surrogate models in Bayesian Optimization, where the goal is to optimize a black-box function that is expensive to evaluate. The GP captures both the function estimate and its uncertainty, enabling exploration vs. exploitation strategies.

Uncertainty-Aware Regression

GPs naturally model predictive uncertainty. This is vital in:

- Medical diagnosis (model confidence matters),

- Sensor fusion in robotics (merging noisy measurements),

- Scientific modeling (where understanding the confidence of predictions is key).

Small-Data Regimes

In cases where data is expensive or scarce (e.g., drug discovery, experimental physics), GPs shine because they can learn complex patterns without overfitting and provide principled uncertainty.

Active Learning

Because GPs quantify uncertainty, they are ideal for active learning — selecting new data points where the model is uncertain to improve learning efficiency.

Gaussian Processes offer an elegant solution to the problem of modeling unknown functions with uncertainty. Their interpretability, flexibility, and strong theoretical foundation make them a powerful tool for data scientists working in probabilistic modeling, especially in safety-critical and small-data domains.

Bayesian Foundations in Modern Data Science

The concepts explored throughout this discussion—Bayes’ theorem, priors and posteriors, likelihoods, conjugate priors, MLE, MAP, and Gaussian Processes—collectively form a foundational perspective on statistical inference. These ideas extend beyond isolated techniques; they represent a systematic approach to learning from data in uncertain settings. Bayesian methods offer a coherent framework for incorporating prior knowledge, updating beliefs based on observed evidence, and reasoning in a probabilistic manner.

Among the earliest and most accessible examples is the Naive Bayes classifier, which applies Bayes’ theorem to supervised classification tasks. Despite its assumption that features are conditionally independent given the class label, the model often performs well in practice, especially in high-dimensional problems like spam detection or document categorization. It constructs a posterior distribution over class labels:

\[P(C \mid x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) \propto P(C) \prod_{i=1}^n P(x_i \mid C)\]In this formulation, the prior class probabilities \(P(C)\) and the conditional likelihoods \(P(x_i \mid C)\) can be estimated using MLE or MAP techniques. If needed, conjugate priors can be used to incorporate prior knowledge and simplify inference. While simple, the model’s efficiency, transparency, and probabilistic interpretation make it a useful baseline in a variety of real-world systems.

More expressive probabilistic modeling is possible when one relaxes the independence assumptions and considers the dependency structure among variables. This leads to the framework of Bayesian networks, which use directed acyclic graphs to represent conditional dependencies. The joint distribution is factored as:

\[P(X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n) = \prod_{i=1}^n P(X_i \mid \text{Parents}(X_i))\]Each node in the graph corresponds to a random variable, and each edge indicates a dependency. This decomposition generalizes the ideas seen in Naive Bayes by allowing richer structures that capture causality, interaction effects, and shared influences. Parameters in Bayesian networks can be estimated using MLE or MAP, and conjugate priors are often employed to simplify learning, especially in the presence of missing or noisy data. These models are well-suited for complex reasoning tasks, such as medical diagnosis, credit risk modeling, and user behavior analysis.

While the models discussed so far rely on explicit parameterizations, Gaussian Processes offer a non-parametric alternative by placing a prior over the space of functions themselves. Rather than defining a fixed number of parameters, a Gaussian Process assumes that any finite set of function values follows a multivariate normal distribution. This is particularly valuable in regression tasks where predictive uncertainty is as important as the predicted value.

A Gaussian Process model, once conditioned on observed data, yields a posterior distribution over possible functions, complete with mean predictions and confidence intervals. The choice of kernel function encodes assumptions about smoothness, periodicity, or other properties of the underlying function. This makes Gaussian Processes especially useful when working with small datasets, where flexibility and uncertainty quantification are critical.

A prominent use case for Gaussian Processes is in Bayesian optimization, a strategy for optimizing functions that are expensive or difficult to evaluate. Here, a GP acts as a surrogate model that approximates the true objective, guiding the selection of future evaluations based on both predicted values and uncertainty. This methodology has become a standard tool in hyperparameter tuning, experimental design, and materials discovery.

The broader value of Bayesian modeling lies in its capacity to quantify and propagate uncertainty. In domains such as healthcare, autonomous systems, and finance, uncertainty-aware predictions support better decision-making under risk. For instance, posterior class probabilities from a Naive Bayes model can inform risk thresholds in a classifier; MAP estimates provide regularization by incorporating prior constraints; and Gaussian Processes yield confidence bounds that reflect the limits of available information. These capabilities are not peripheral—they are central to deploying models that must make informed decisions under real-world conditions.

As we close our discussion on Bayesian inference, the natural next step in our learning journey is to explore how statistical inference—particularly in its frequentist form—shapes decision-making in data science. In the upcoming part of this series, we will dive into the core principles behind A/B testing, sampling techniques, confidence intervals, and hypothesis testing frameworks such as the Z-test, T-test, and ANOVA. We’ll also unpack concepts like p-values, statistical power, and Type I/II errors to understand how to validate results under uncertainty. These tools are critical when measuring the effect of product changes, analyzing experiment results, or quantifying the impact of features in machine learning workflows. If Bayesian inference teaches us how to update beliefs, classical inference equips us to rigorously evaluate them—and together, they form a powerful toolkit for modern data science.